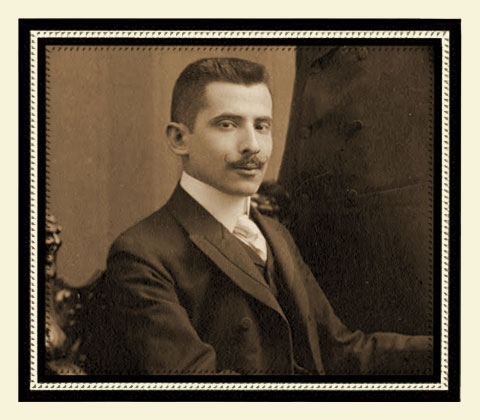

Vienna, 1879 — New York, 1977

Stefan Zweig’s brother, businessman

Two years older than his brother Stefan and following the patriarchal tradition, Alfred was groomed from an early age to take over the family’s factory in Reichenberg, today Liberec, (north Bohemia, after 1918 Czechoslovakia and, from 1993, the Czech Republic).

The father, Moritz, the son of a merchant and originally from neighbouring Moravia, at the age of thirty created a small textile factory, which over three decades became one of the most important in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Now rich, he moved to Vienna upon his marriage to Ida Brettauer, from a family of bankers and textile entrepreneurs. He played piano, spoke French and English, was discreet, moderate, never borrowed nor loaned. In the comfortable apartment at 14 Schottenring two sons were born and the family soon moved to the larger and more sumptuous Rahaustrasse, 17.

After finishing secondary school, Alfred was sent to work running the factory while Stefan – stubborn just like his Italian mother – bravely resisted paternal pressures to follow his brother. Family history vaguely suggests there may have been physical confrontations between the father and younger son because of these differences. He resigned himself when his 20 year-old son’s name started to appear in print.

Clearly Alfred took after the father and Stefan their restless and dominating mother. But there were aunts, grandparents, governesses and even tutors (Stefan needed one to overcome his trouble with arithmetic and physics). When Moritz was operated on in 1903 and was forced to stop work for almost a year, Alfred assumed all responsibilities, since one of the oldest employees left the company at that very moment to set up his own business. At the age of 24, Alfred became the company’s sole signatory (Einzelprokurist) and, the following year, public shareholder (öffentlicher Gesellschafter), positions rarely occupied by someone so young.

The difference in temperament, taste and careers didn’t prevent the brothers from sharing friendships, activities and victories. At the premiere of the Das Haus am Meer, in October 1912, only his brother and old friend Victor Fleischer were with the author.

Almost daily they met in their parent’s house for a meal because the kitchen in Stefan’s apartment at Kochgasse 8 was an extension of the office.

Only Alfred knew of his brother’s affair with Friderike, a married woman, and kept it secret until the couple allowed differently, charging him with the task of preparing their mother for the “official” announcement (in 1918). However he did again warn his brother about the dangers of becoming involved with a woman, the mother of two daughters and lacking in resources to educate them. He feared his brother would try to adopt them. As a businessman he felt obliged to be a realist: he doubted his future sister-in-law’s literary gifts or his brother’s ability to take care of himself.

Ida’s affection for her daughter-in-law and the way in which Friderike took on the role of his brother’s protector convinced him to set aside his suspicions. And Stefan never again made jokes about “the enemy Alfred”.

At the marriage ceremony in Vienna (January 1920), by power of attorney and without the presence of the groom, who stayed in Salzburg, Alfred served at witness. (q.v. Zweig, Friderike). But he thought about nthing but business and amorous adventures. It was not by chance that he arrived at his parent’s home with a fiancée, Stefanie Duschak soon to become Stefanie Zweig. With the younger son and Friderike in Salzburg, the new daughter-in-law starts taking care of the lives of Ida and Mortiz at the apartment on Garnisongasse.

Soon after Stefan’s last visit to the factory (1921), the brothers decide to turn the company into a modern corporation. Alfred becomes president of M.Zweig Mechanische Weberai (mechanical weaving mill) and Stefan is made administrative advisor, each with 45% of the capital, the rest subscribed by a bank in Prague. As Director-General (what today would be CEO), Alfred received a lifetime annual salary of 400,000 Krone. Thanks to this, the walls of his Vienna apartment were covered in Dutch master oil paintings.

They never had patrimonial divergences. As Zweig said with some amusement: all Alfred ever thought about was keeping the books, and he just wrote them. It was an extremely advantageous arrangement for the writer: it gave him the financial freedom to enjoy the spiritual freedom he valued so much.

Moritz’s death in 1926 in no way altered the company’s new arrangements, which were made precisely due to his advanced age. This only acerbated their mother’s habit of commanding others, now with no subjects to command.

To mark Alfred’s 50th birthday, the brother dedicated to him the play Das Lamm der Armen (tragicomedy in three acts and nine scenes about Napoleon’s Egypt campaign), published in 1929 and premiered with great success the following year. For his 50th birthday two years later, as well as a visit from his brother there was a letter, one of the few we still have: “As the sons of our father we inherited a certain personal detachment... I can only see what a blessing it is that we didn’t have children... Our only obligation is to live decently until the end of our days and we shall certainly manage that...”

Alfred accompanied the unpleasantness between his brother and his step-daughters, the move to London, the appearance of Lotte, the tos-and-fros of the separation from Friderike, but their communication mostly took place by phone. The businessman wasn’t much of a letter writer (the few he kept were destroyed after his death by his order). In a hurry and practical, he preferred real time communication.

When in 1934 the house in Salzburg was searched by the Austrian police looking for guns, Stefan returned to London and asked his brother to make the official announcement of his departure from the country. The annexation of Austria by Germany (1938) didn’t take Alfred by surprise: the factory was in Czech territory and he had adopted the neighbouring country’s citizenship a long time ago. He had no trouble obtaining a visa for entering Switzerland (he left Vienna two weeks after the arrival of the Germans) and even managed to get authorization for their mother to go to Paris. Ida Brettauer didn’t want to go: deaf, sick, little strength for the Herculean effort of packing up the Garnisongasse apartment, she preferred to wait in Vienna. The cousin Egon Frankl was called upon by Alfred to supervise the old employees taking care of the firm. A nurse supervised medication, but as an Aryan wasn’t allowed to stay overnight in a household where a Jewish man was staying. Egon was forced to sleep elsewhere. Alfred phoned from Zurich every night and then sent news to the brother in London. For as long as she could, Ida went on walks every day. Soon, the Nazis forbid Jews from sitting on park benches.

After 10 days unconscious, Ida died alone and was buried in the Jewish part of the main cemetery beside Moritz. The only relation still there, cousin Egon, whom Ida considered a third son, then moved to the Garnissongasse apartment, where he died the next year.

The brothers were reunited in early 1939 in New York, when Stefan, accompanied by Lotte, began a coast to coast lecture tour. Alfred and his wife Stefanie were comfortably installed right by Central Park (18 W 70th St), as usual more concerned with themselves than with the turbulence around them.

They met again in June the following year in the same city when Stefan, terrified at the possibility of the invasion of England, began the unfortunate rush to flee the war.

In 1941, when Stefan and Lotte returned to South America and the writer sought refuge in some library to finish the Brazilian book, he decided to get away from the hubbub of New York, but chose Yale, in New Haven, Connecticut, so as not to be too far from his brother. They met several times and on once occasion he witnessed the casual encounter between Stefan and Friderike, the first since she’d escaped France. He didn’t approve of the former couple’s enthusiasm at the unexpected encounter.

Soon after, Stefan began to complain with some regularity at his brother and sister-in-law’s detachment, when he wrote to Hannah Altmann about her daughter, Eva, Lotte’s dear niece who had left England under Luftwaffe bombardment to stay at a pension for refugee children not far from Manhattan. Stefan was counting on the loving care that Alfred and Stefanie had for the girl. He was disappointed, but he didn’t quarrel with his brother. They were different, they always had been.

Their final encounter took place during this New York stay, before the last departure for Brazil: they dealt with business and Zweig left him two Rembrandt drawings he’d brought from Bath.

Alfred wasn’t included in the circle of 21 friends to whom Stefan bid farewell by letter or card. But he was favoured on Saturday, 21st February, two days before the suicide, with a hopeful letter from his brother, telling him they’d decided to extend the rental of the bungalow in Petrópolis for another six months. This was certainly written on the 10th, when Lotte sent the same news to the Altmanns.

Thus protected by his brother, the bad news only reached Alfred two days later by radio. He lived for another 35 years.

The difficulties between Friderike and the ex-brother-in-law persisted. Alfred was furious when Friderike began to be treated like Stefan’s widow. De jure she wasn’t (they’d been divorced for four years), but she was the de facto widow, not only in the vast circle of friends, but the enormous community of German-speaking intellectuals who took refuge in the United States, Palestine and Argentina. And when the first edition of the biographical profile written by Friderike was published (1946 in Argentina and Brazil and 1947 in Stockholm), Alfred tried to have it embargoed, claiming it contained offences to his family’s honour.

He attempted a reprisal: through the Altmanns he got in touch with Richard Friedenthal (q.v.), who was also living in London, and invited him to write an authorized biography, promising him documentation, unpublished letters, photos. The writer was having to spend long periods in sanatoriums in Switzerland and so wasn’t enthusiastic. In 1950, to counterbalance the influence in American academic circles, he offered substantial support for the foundation of an Austrian entity, the Internationale Stefan Zweig Gesellschaft, based in Salzburg, now a worldwide authority. He ordered his own papers to be destroyed upon his death.

He was complicated, more so than his brother.

Address listed: 18 West 70th Street, New York. Tel. Endicott 2-3766.