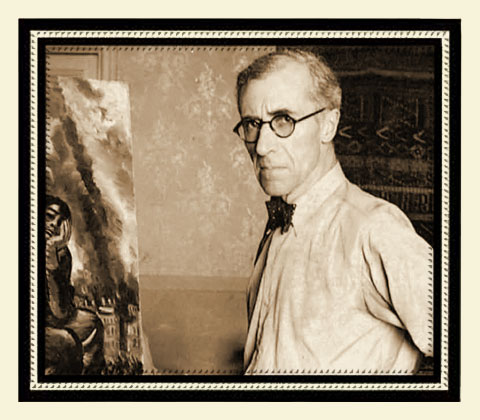

Blankenberge, Belgium, 1889 — Avignon, France, 1972

Graphic artist, wood engraver, illustrator

Working as an illustrator for newspapers and magazines, Masereel met Stefan Zweig in Switzerland in 1917 when he was fighting for peace together with other intellectuals from all over Europe.

“A solid, sweet figure, a grave look behind the spectacles, like Verhaeren, only wears thick corduroy clothes, in the style of a labourer. I was attracted to him from the first minute...” “Marvellous, I especially like his serious manner and the way he listens. I never expected so much from someone...” “...A comfort [in these difficult days]: so clear, pure, so good. I’m aware that there are few people around me that I love. He is nothing but goodness, energy, the most wonderful combination.”

Notwithstanding his hard, rough appearance, Masereel was the dearest character to appeared in the diaries. In his letters to Friderike he didn’t hide his affection for this vigorous artist, brimming over with goodness.

Masereel is considered by artists of the calibre of Will Eisner and Art Spiegelman to have invented the graphic novel through his large collection of “novellas without words”, produced during the pacifist crusade. The group came together around two newspapers, Demain, founded by the mercurial Guilbeaux (a Communist who converted to anti-Communist) and La Feuille, where Masereel published daily woodcuts about the horrors of war.

The central figure was Romain Rolland, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1915. Also present were Russian revolutionaries such as Lenin and Trotsky, awaiting the fall of the Czar, the Irishman James Joyce writing in English but intensely anti-British in spirit, the composer Ferruccio Busoni and many others.

Masereel illustrated the monumental Jean Christophe, by Rolland, with 666 woodcuts, and also Zweig’s pacifist novella Compulsion, using the figures of Stefan and Friderike as models for the two protagonists. For a collection of complete works in Russian (1926) he created a faithful portrait of Zweig which has been reproduced hundreds of times to this day. He also illustrated the works of other great authors, such as Émile Zola and Thomas Mann.

Over the next 23 years they were very close in Paris, Nice, Ostend and Salzburg, until 1940 when Zweig left Europe for the New World. And even once safe on the other side of the Atlantic, Zweig tried obsessively to obtain for Masereel entry visas for Brazil, Argentina, Colombia and the United States. All in vain: perhaps because he was too anguished and depressed.

During the German occupation he hid in small towns in the French countryside. He wasn’t Jewish, nor a Communist, his socialism was no different from that of Rolland. Neither of them was hounded by the Gestapo. In Zweig’s memoirs he is mentioned on three occasions and in his first collection of essays, Begegnungen mit Menschen, Büchern und Städten [Encounters with People, Books and Cities], Zweig included a piece about Masereel.

He portrayed people in their isolation in modern civilization, while at the same time offering possibilities for action. In his oeuvre of woodcuts he produced series such as 25 Images of a Man’s Passions (1918), the 80 works The Face of Hamburg and the 100 of the cycle The City (1925). From 1947 to 1951, he lead the painting classes at the recently-founded School of Arts and Crafts in Saarbrücken. In Switzerland in 1953 he founded Xylon – International Society of Wood Engravers. Between the end of the Second World War and 1968 he published a series of engravings representing variations on a particular theme. He was the subject of numerous exhibitions and a member of several academies of the arts. His name appears at the head of institutions such as the Frans Masereel Centre, in Kasterlee, Belgium, and Masereelsfonds, an entity promoting the Flemish language which was originally associated to the Belgian Communist Party and which nowadays has an independent progressive disposition.

Address listed: 30 Rue des 3 Faucons, Avignon.